The Woodbank Mystery

Mischief in a private mine

F22015 - first published 13th August 2022

In response to the fuel shortages that followed the second world war, many small-scale coal mines were sunk to exploit small pockets of coal that lay close to surface but had previously been overlooked. Many off these little mines were set up as small businesses owned by groups of miners, When the coal industry was taken into public ownership on Vesting Day - 1st January 1947, small mines employing less 30 men continued as private companies, operating under licence from the National Coal Board.

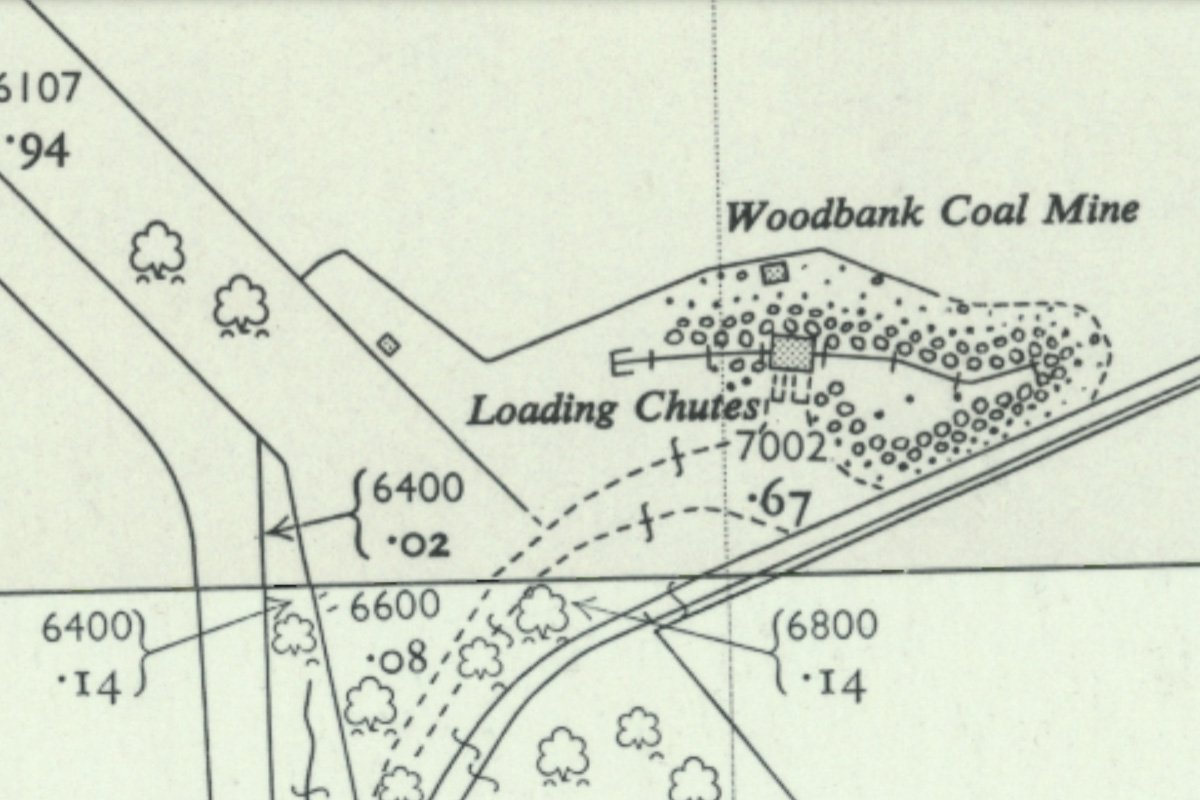

Woodbank mine lay in the peaceful countryside between Armadale and Bridgecastle, picturesquely sited among trees beside the Mad Burn. The enterprise was started in 1947 by three miners from Westfield, who later brought in two further partners when capital ran short. It was a simple operation with a drift mine, about four feet high, dipping to the west, presumably to reach the Colinburn coal, At the time of “the incident” the mine extended just 380 feet, employed 24 men, and produced about 40 tons of coal each week. The operation seems to have been run on a shoe-string and it was later admitted that the mine “was doing very badly indeed” at that time.

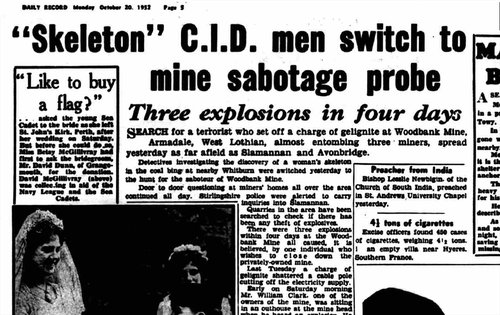

On Tuesday 15th October 1952 there was an explosion that damaged a pylon that carried the electricity supply to the mine. This halted production for two days, but surprisingly little seems to have been made of the incident.

Early on the following Saturday, while three night-shift workers were at the coalface, there was a further explosion that once again cut off the electricity supply, and with it pumping and ventilation to the mine. While the police were being phoned there was a second explosion close to entrance to the mine, causing considerable damage. The three miners had to crawl to safety through the rubble. This extraordinary event naturally attracted the attentions of the press. National newspapers spoke of a “man with a grudge adopting terrorist tactics”. Superintendent Cook of the Lothians Police was soon on the case, assisted (according to the papers) by Skipper, a specially trained police dog. An additional night watchman, some high power lamps, and two further Alsatian dogs, were brought in to deter any further attacks. It was reckoned that a miner was responsible for the terror as the gelignite charges used “had been expertly made-up and placed where they could do most damage”. The police began to work through a list of 80 people who had been employed at the mine over the previous two years.

About two weeks later, at 2am on Sunday 2nd November, a further explosion (said to be felt three miles away), again destroyed the pole carrying the electricity supply to the mine. One of the night watchmen, a 20 year old miner called Douglas Smith, telephoned the police to report this fourth explosion. In later questioning, Smith accused a second night-watchman on duty at the time for setting off the explosion; it was subsequently revealed that this man was asleep at the time. Smith then claimed that he had been given £20 by two men to light a fuse on a concealed pile of gelignite. However these two mysterious men were never traced.

Smith was sentenced to six months in jail for “unlawfully and maliciously caused by gelignite an explosion likely to cause serious injury to property”. It seems that no charges were ever brought for the earlier explosions, and in mitigation it was explained that Smith had suffered a difficult childhood, had been raised by his grandparents, and had worked in mining since leaving school at the age of 14.

From the information shared in newspapers it remains unclear whether the explosions were down to Smith alone, whether there were dark forces trying to force the mine owners out of business, or whether there was a different explanation.

All the publicity surrounding the explosions attracted the attention of officialdom, and in the following year the five mine owners faced two sets of charges both of which carried the prospect of very significant fines. The partners had traded as the Woodbank Mining Co. Ltd without officially registering the name, however the sheriff concluded that they were “not a fly-by-night firm” and the offence was “just ignorance of the law” Charges brought under the explosives regulations revealed that the explosives store at the mine was too small, with no effective lock on the door and no fence around the mine to prevent trespass. It seems that anyone could help themselves to gelignite. Again, the sheriff concluded that the partners were “a small band of respectable men who had struck out to make a living in a perfectly legitimate manner”, and issued only a token fine.

Coal continued to be worked from the little mine in the woods until 1965.

See also Woodbank mine