Mary and the Ballencrieff Pits

An early colliery near Bathgate

F22016 - first published 15th October 2022

Mary Baxter was ten years old when interviewed by the gentleman from the Royal Commission. She had already worked underground for two years, hauling coal at the Ballencrieff colliery. Mary descended the pit at four o'clock in the morning with her mother, cousin and brother. Mother would heugh coal until about midday, when she returned to the surface to attend to a husband who had been unable to work for the last 12 years. He was described as having “failed in his breath”; lung disease was common in mining communities at that time. The children were left underground for the remainder of the day, hauling the coal to the pit bottom. Mary confided to the reporter “I cannot sew any as I am left-handed”, but added proudly “sister Helen can sew her pit clothes and make letter on the paper”.

Mary's mother Margaret was also interviewed. She was then 50 years old and had been forced to take over the duties of a collier when her husband became too weak to work. Mary was the youngest of her nine children and she had “been obliged to work when in family way till last hour.” She felt that mining was not fit work for women.

The Royal Commission Report of Children in the Mines was published in 1842, and contained heart-wrenching accounts of the miserable lives of women and children throughout the mining districts of Britain. It was especially powerful as it captured the actual words spoken by children like Mary. The report pricked the conscience of Victorian society and led to the 1842 Coal Mines Act, which made work underground a male preserve. The act may have assuaged Victorian concerns for decency and Christian morals, but did less to address the poverty and inequality that lay at the root of the problem.

During the late 18th and early 19th century, a great line of limestone quarries were excavated across the Bathgate hills. Kilns were built close-by where chunks of limestone were burned with coal to produce a powdered lime, This lime was of great value in improving and fertilising land, but this was a seasonal demand, and kilns only operated during certain times of the year.

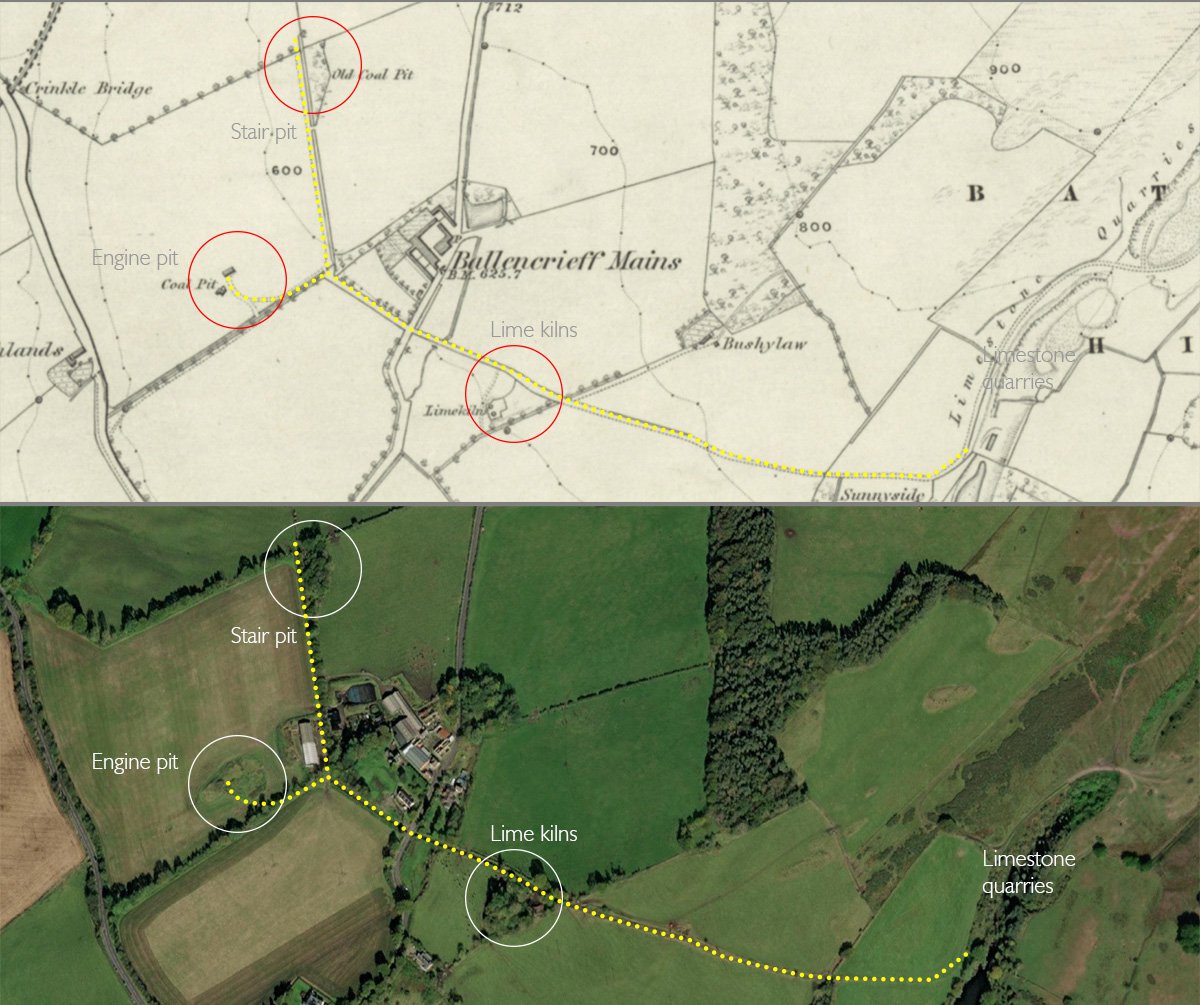

Forrest's map of Linlithgowshire, dating from 1818, shows a lime kiln sited a little north of Ballencrieff toll on the road between Bathgate and Torphichen. A trackway links the kiln eastward up the burn to the great limestone quarries, and westwards past Ballencrieff Mains to two coal pits; most likely the Ballencrieff colliery where Mary and her family once laboured. One pit is marked “coal engine” suggesting that a steam engine once hauled coal to the surface there, while the other is referred to elsewhere as a stair pit - a shaft fitted with ladders, requiring a laborious climb to the surface.

The reporter to the Royal Commission also interviewed Alex Turner, the overseer at Ballencrieff colliery who explained something of the workings of the pit. Most of the coal produced was consumed in the limekilns (it was probably too sulphurous to be used as a house coal), and therefore coal mining was also a seasonal business. Few miners were employed all year round. The proprietors seemed to have had little opinion over who worked in the pit, stating “our colliers employ whom they please, males or females; and as our mine is entered by a bout gate, the people work as they please”. The term “bout gate” might simply describe a round-about route, suggesting that many colliers might come and go out of official view through the stair pit. The long climb would be an additional ordeal at the end of the working day.

The works were abandoned prior to 1855 when the first OS maps showed only a few derelict remains marked as “old pit” or “old limekiln”, Rather wonderfully, some of these traces still survive nearly 170 years later. The stone arches of the limekiln still stand firm beneath a jungle of undergrowth, and cattle are still herded along the tracks that once linked it to quarries and coal pits. The site of the engine pit remains as an island of rough ground within a grazed field, and a mound among trees in the corner of a field marks the site of the stair pit. These traces form part of a beautiful green landscape on the slopes of the Bathgate hills. The spectacular views over the country to west are now enjoyed by holidaymakers in glamping pods, sheltered by the trees that mark the site of the stair pit. It's a terrible contrast to the dark underground world that Mary Baxter would have known.

We don't know what happened to Mary, or whether she lived long enough to raise her own family. Perhaps she lived a happy life; perhaps she is your ancestor?

See also Ballencrieff - old pits

Ballencrieff limekiln. See also Ballencrieff - old pits for images of the pit sites.