Fawnspark Mine and the Tunnel beneath the Canal

The difficult history of Hopetoun No. 41 pit

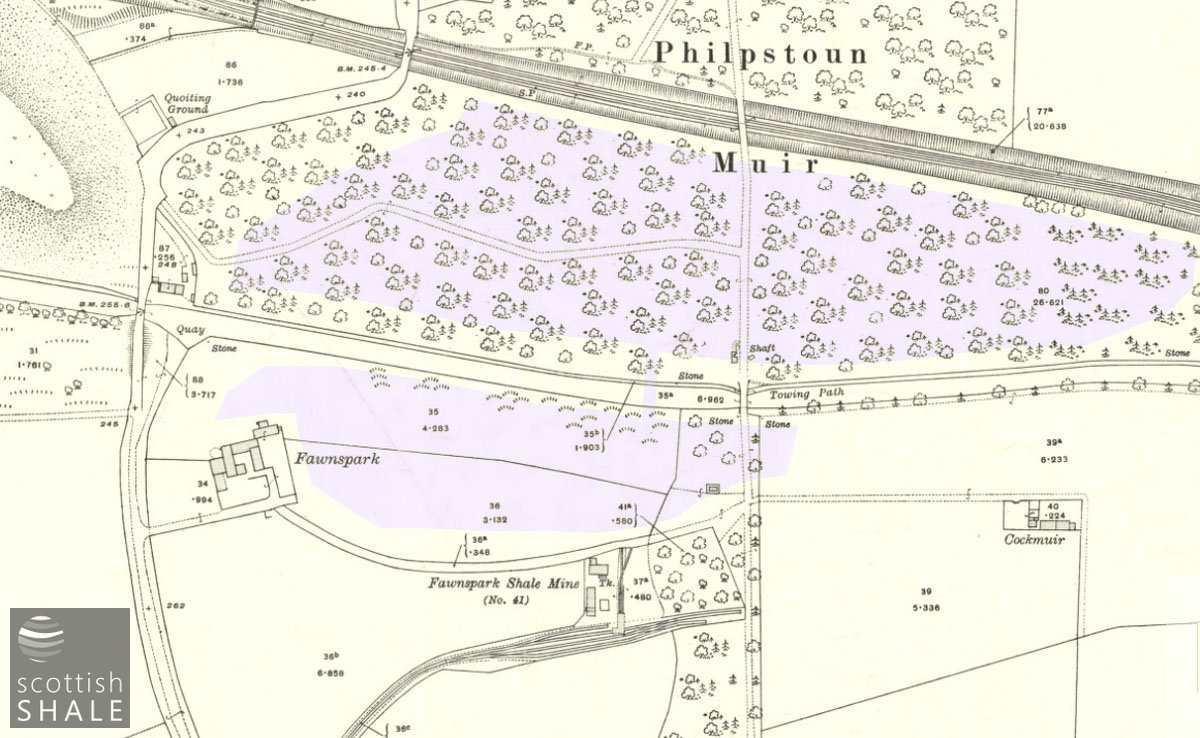

25" OS map c.1914, courtesy of National Library of Scotland, with the approximate extent of underground workings marked in colour.

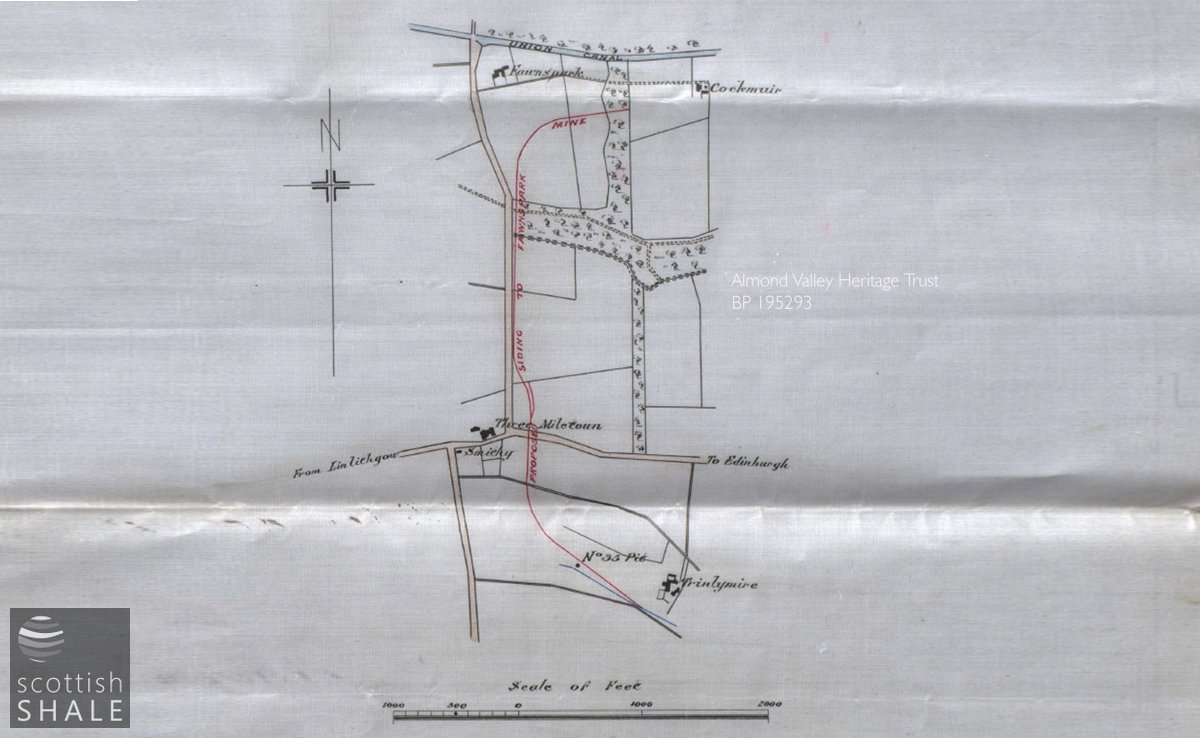

In 1906, Young's mineral railway was extended from their No.35 Threemiletown pit to Fawnspark No.41 mine. Parts of the low embankment beside the Philpstoun Mill Road survived into the 1980's.

F19039, first published 27th October 2019

Fawnspark shale mine (officially known as Hopetoun No.41) was the most northerly of the many shale pits operated by Youngs Oil Co. It was connected to Young's oil works at Hopetoun and at Uphall by a five mile long mineral railway that wound its way through the countryside by way of Ecclesmachan, Glendevon and Threemiletown. Interviewed in 1983, Mr J.D. recalled that the company's train left the level crossing at White Gates in Uphall (now site of the Arnold Clark garage) at 6.00am each day, conveying miners to their place of work in simple window-less carriages with hard wooden seats. Workers would alight at various points along the route and walk to nearby pits; the final few travelling all the way to end of the line at Fawnspark.

In 1903, the Earl of Hopetoun granted a mineral lease to Young's Oil Co entitling them to work the minerals that lay beneath the lands of Fawnspark. Shale occurred only a small part of the lands immediately south of the Union Canal, and in an area beneath woodland on the northern side. It was always known that reserves were restricted and working conditions would be difficult, however the good quality of the Broxburn shale, in a seam five and a half feet thick, promised to make the operation worthwhile.

The Broxburn shale outcropped in the field to the east of Fawnspark farm house. A mine was driven from the outcrop, heading northward and following the strata into the ground at an angle of one in ten. The main roadways were subsequently extended beneath the canal to reach the area of shale that lay beneath the plantation on the northern side.

1n 1905 Young's wrote to the canal company (the NBR) informing them that their workings now extended to within 40 feet of the canal and that they now intended to mine beneath it. The NBR accepted that roadways pass beneath the canal, but warned against working shale from beneath the bed of the canal. The oil company went ahead and drove a brick-arched tunnel at a depth of only 21 feet beneath the canal and extended workings beneath the plantation on the northern side, Conditions in this area were difficult. Large fissures appearing in the ground and by 1910, when many of stoops had been worked out, the ground surface had already subsided by about four feet. Fences were erected to prevent walkers and huntsmen entering the plantation, which had been a regular haunt of the local hunt.

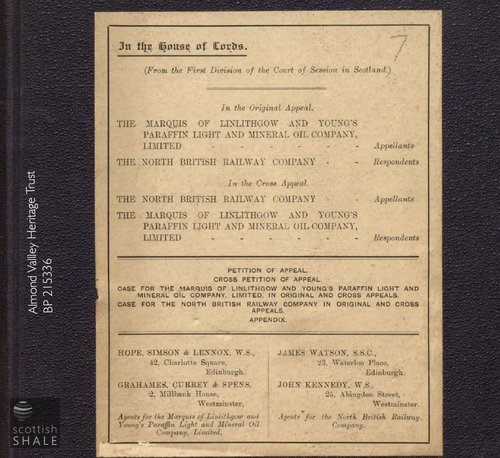

Correspondence continued between the Young's and the NBR regarding the shale that remained intact beneath the canal and to 40 feet either side. It was usual practice for railway companies to purchase the minerals beneath their tracks in order to safeguard them from subsidence. The NBR maintained that this did not apply to Union Canal, as it was constructed under an act of 1817 – at which time oil-shale had yet to be discovered and therefore could not considered as being a mineral. A lengthy succession of court actions took place, culminating in an appeal to the House of Lords.

Leading experts and learned professors were called to testify at these grand hearings. All agreed that extracting shale from beneath the canal was not a good idea. At one point the shale was only 14 feet beneath the bed of the canal, and the ground was prone to fissures. Because of this, one expert described the potential consequences to those working beneath as “hair-raising”, and suggested that collapse of workings would have much more serious consequences to those mining the shale than those navigating the canal. The central issue of who should carry the cost of keeping the shale in place pivoted on the argument of whether or not oil-shale was considered a “mineral” at the time the canal act was drawn up. Lengthy expert testimonies provided detailed historical accounts of the oil industry from earliest times (a great resource for the modern historian) and lengthy descriptions of chemistry and geological taxonomy. Ultimately is was decided that the canal company - the North British Railway - should pay to keep the shale in place. In hindsight, the effort and expense of such elaborate legal actions seem quite out of proportion to the small advantage gained – it was a point of principle.

No.41 mine was worked-out and abandoned by 1927. Today the canal and the lands forty feet to either side stand proud above the surrounding landscape. The woods to the north remain a mess of slopes and hollows, with loose pieces of shale still scattered among the trees. There are references to this area as the “Fawnspark opencast” - perhaps suggesting that once mining of the main Broxburn shale was complete, the inferior seams of Gray and Upper Broxburn shale that lay at a higher level were worked from the surface. To the south of the canal, the settling of the ground clearly defines the extent of mining, and some low-lying parts have become marshy and uncultivated in recent years. Little remains to indicate the site of the pithead area of the mine, and a low embankment that once carried the railway line was cleared during the 1980's (or thereabouts). It's hard to imagine that there was ever a level crossing over the main Linlithgow to Winchburgh road close to Threemiletown, or that ramshackle trains once brought Uphall folk to work each day beneath the fields of Fawnspark.

View from close to the site of Fawnspark mine, looking west towards Fawnspark farm, the two bings of James Ross & Co's Philpstoun oil works, and the bridge carrying the B8046 Philpstoun Mill Road over the Union Canal. The rough ground centre-right is the consequence of mining subsidence.

Approximate site of Fawnspark mine, looking eastward.

Looking north towards the canal, the fence-line reflects the drop of the land surface due to mining subsidence. The underground roadway linking the two areas of mining will have passed beneath the canal close to this point. The brick arched tunnel which provided this link will doubtless still exist, 21 feet below the bed of the canal.

In the woods to the north of the canal there remain steep sided slopes scattered with a lumps of shale.

Pits created by subsidence or subsequent opencast quarrying, in the woods to the north of the Canal.