Boghead House, Titlarks, and Swallows.

The pastimes of Thomas Durham Weir

F22013 - first published 15th July 2022

Thomas Durham Weir, “the esteemed and venerable laird of Boghead”, died in 1869 at the age of 77, All accounts speak of him with affection, making frequent reference to his affability, kindness and compassion. Curling was one of his great passions, and for many years he served as president of Bathgate Curling Club. Thomas seems to have been in his element at curling club dinners where, surrounded by the local great and good, numerous toasts were enjoyed between a succession of witty speeches and jolly curling songs. Here he could exercise his “felicitous and mirth-creating style”. It was said that upon such occasions “his little dapper figure was full of life and animation. He possessed a continuous flow of good spirits, and his wit and humour was sparkling and spontaneous. He had a kindly word for all.”

It was never expected that Thomas would inherit the Boghead estate. He had served an apprenticeship as a banker, with the intention of earning a living in the world of business. His mother's family, - the Durhams - had been lairds of Boghead since 1702, but in the absence of a direct male heir, there was dispute over the line of succession. On the death of his grandfather, Thomas Durham Weir rather unexpectedly inherited the Boghead estate and found himself enjoying the quiet and independent life of a country gentleman.

The Boghead estate extended over 321 acres, lying to the south of the road between Bathgate and Armadale. The original laird's house probably lay close to Little Boghead; beside the Whitburn Road, however in about 1812 a new mansion-house was built on a hill-top location about half a mile to the west. It was described as a “plain commodious building, two storeys high”, however what it lacked in decoration was more than made up for by the beauty of the ornamental parkland that surrounded it

The main vista eastward from the house overlooked a strip of formal gardens and then open parkland that swept down the hillside to reveal views across the town of Bathgate and beyond to the Bathgate Hills. The parkland was carefully contrived to provide pleasing views in all directions and, a little distance from the house, a substantial walled garden and its glasshouses provided pleasure and produce.

Thomas took on many of the duties expected of a local landowner. He served as Chair of parochial board, (and was by all accounts a compassionate benefactor of the poor), and was later appointed as deputy-lieutenant of Linlithgowshire. Such duties do not seem to have occupied a large proportion of his time however. The commercial management of the estate was devolved to his nephew, Alexander Robertson, a prominent accountant who served as his factor. It will have been Alexander who managed the lease of the estate's minerals to James Russel & Son which from1849 paid a substantial royalty for every ton of the famous Boghead Gas Coal that was mined beneath the estate. By the mid 1850's over 15 pits had been sunk to extract the valuable mineral, forming an arc around Boghead house, but retaining a respectful distance to avoid intruding on the views from the laird's residence. The oil and gas-rich Boghead Coal attracted the attentions of James Paraffin Young, who chose to set up his first oil works at a site in the easternmost part of the estate. Close by, the new village of Durhamtown was established to house the huge influx of labour required to serve the flourishing mines. This village of over 70 homes (the property of Thomas Durham Weir) was established with the best of intentions. It was served by two shops and a school for140 pupils. One visitor remarked how “even the more ragged of the little urchins, quickly and correctly solved some very difficult questions in arithmetic and mensuration.” Areas were patriotically christened Alma Place and Cardigan Place after the ongoing Crimean War. Unfortunately Durhamtown itself soon achieved a reputation as a battlefield. There was sectarian tension between a workforce drawn from throughout Ireland and Scotland, with frequent acts of violence and some small-scale riots. Men were beaten with road-stones wrapped in handkerchiefs, there were stabbings, travellers were pulled from their horses and robbed, and a high-profile murder sealed the village's reputation. A shebeen was discovered, and there were a number of unexplained deaths (perhaps related to consuming the produce of the shebeen?). Thomas Durham Weir originally named the settlement Durhamville; however this French affectation was soon corrupted to the unflattering “Durham-vile” and Thomas ruled that it be re-christened Durhamtown. This was soon became scotticized as Durhamtoun

While the clamour of industry raged around the margins of the Boghead estate, most evidence of this remained hidden from the residents of the big house who, despite smoking chimneys just beyond the horizon, continued to enjoy green and pleasant views.

During winter months, when jock frost touched West Lothian's ponds, the sport of curling will have occupied most of Thomas Durham Weir's attentions. In warmer months he will have had time to enjoy his other great passion – natural history – and in particular, the study of birds. Thomas spent hours patiently observing the behaviour of birds and insects around his estate, and in other wild corners of West Lothian. In touch with the leading ornithologists of the day, his observations were incorporated into many publications, and were sometimes shared in the local press.

In one article he described his study of a titlark's nest built beneath a bush on Monyfoot hill (a lost West Lothian place name?) in June 1835, and a similar nest on Balgornie moor observed in May 1839. In each instance a cuckoo laid one egg in the nest of the unsuspecting titlark (now known as the meadow pipit), and when the egg of the much larger bird hatched, the cuckoo chick set about pushing each titlark chick out of the nest so that it received the full attention of the parent birds. He observed that a depression in the shoulders of the cuckoo chick seemed specifically adapted for heaving smaller chicks from the nest – a remarkably advanced conclusion considering that this was long before modern aids to observation, such as CCTV, and some years before the publication of Darwin's theory of evolution.

Thomas' interests extended to rare insects. He described his pursuit of a Peacock's Eye Butterfly near Avontonhouse – remarking that he “pursued the tiny stranger for a long time in the hope of securing it, but these efforts proved unsuccessful.”

Some of his most important observations and experiments helped prove the theory of bird migration; at a time when few believed that tiny birds could travel huge distances each year. In 1859, he observed a pair of swallows nesting beneath the eaves of Boghead house. He netted the male swallow, and tied a tiny written message around one of his legs before releasing it. This distinguishing marker showed that the same swallow returned to same nesting spot over the following three summers. He described it as “one of the most beautiful birds that I have known”. The bird returned the following year, but seemingly with something new tied around its other leg. Despite repeated attempts Thomas was unable to net the swallow, therefore he chose to shoot his “beautiful bird”. The new label on the dead bird's leg bore an address in Madrid. Victorians were great naturalists but had an unfortunate habit of shooting and stuffing the creatures they pursued, pining butterfly to cards, and blowing out eggs taken from nests. Thomas accumulate three huge glass cases filled with over 400 stuffed birds.

The Boghead estate continued in the family following Thomas' death and remained so into the early 1920's. When the house was then sold, Thomas' flock of stuffed birds was presented to Bathgate Academy.

After years of slow decline, Boghead house shared the same fate as many other fine residences in West Lothian and was demolished in 1962. Few traces remain of the house, although the walled garden and dovecot have been allowed to fall into picturesque ruin. Cattle now wander between the rhododendron bushes around the site of the house, and graze on parkland still defined by mature ornamental trees. It's still a beautiful place, and in summer swallows still swoop across the meadows; in all likelihood, the descendants of Thomas' beautiful bird.

View east from garden site, overlooking the parklands

Ruins of the walled garden

Ruins of the walled garden

View towards Falside and the Bathgate Hills

Cast-iron relic and view across parkland

Ford across the burn

Ruins of the walled garden

Approach to the site of Boghead House from the north

Ruins of the dovecot and kennels

View to the east

Swallows swoop across the meadow in front of the site of Boghead House

More swallows in front of Boghead House; with just a little multiple exposure photo-trickery

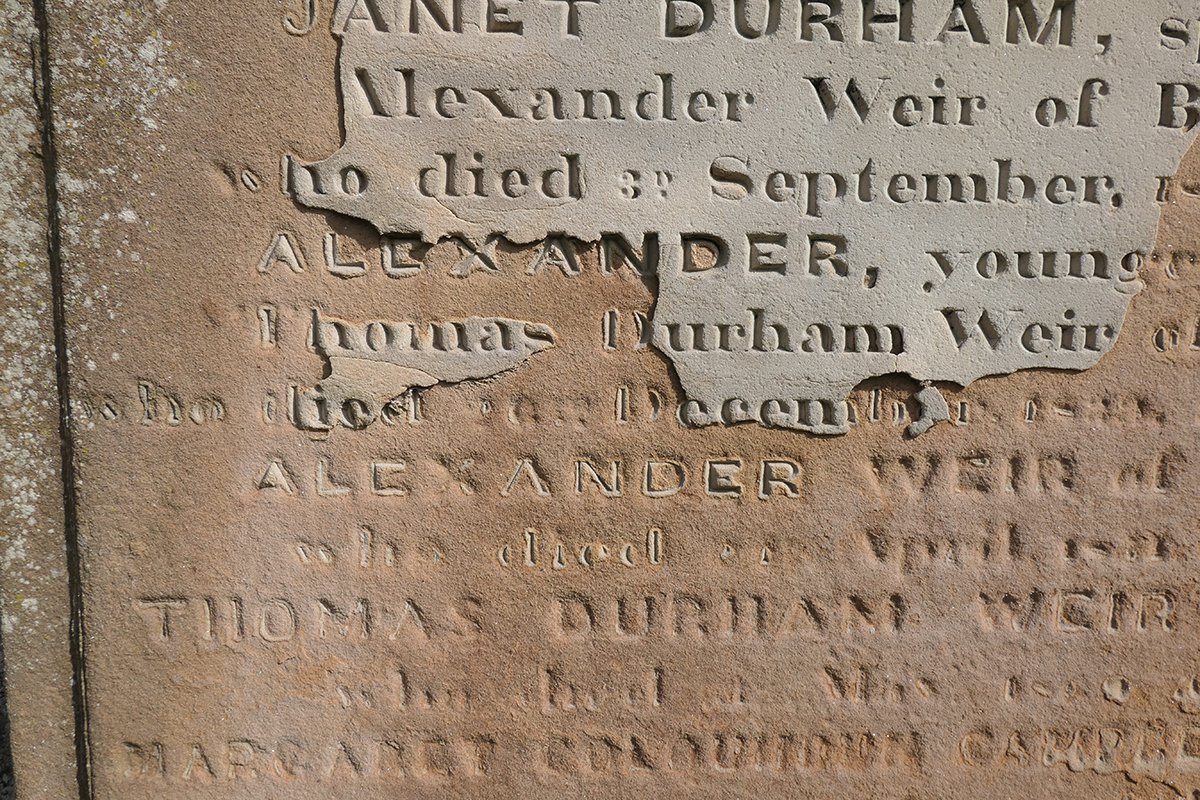

The Durham family memorial within Bathgate old kirk

A little birdfood left to nourish any passing titlarks

Nothing lasts - the inscriptions are flaking away