A Hundred Holes in Cairnpapple Hill

Early Coal Workings in the Bathgate Hills

F22019 - First Published 13th November 2022

The banks, ditches and mounds on the summit of Cairnpapple Hill mark out a focus for ritual and belief that extends back for more than five thousand years. On the western slopes of Cairnpapple, in the area known as the Hilderston Hills, there are a further group of earthworks, but of a much more recent origin, and representing a far more mundane purpose.

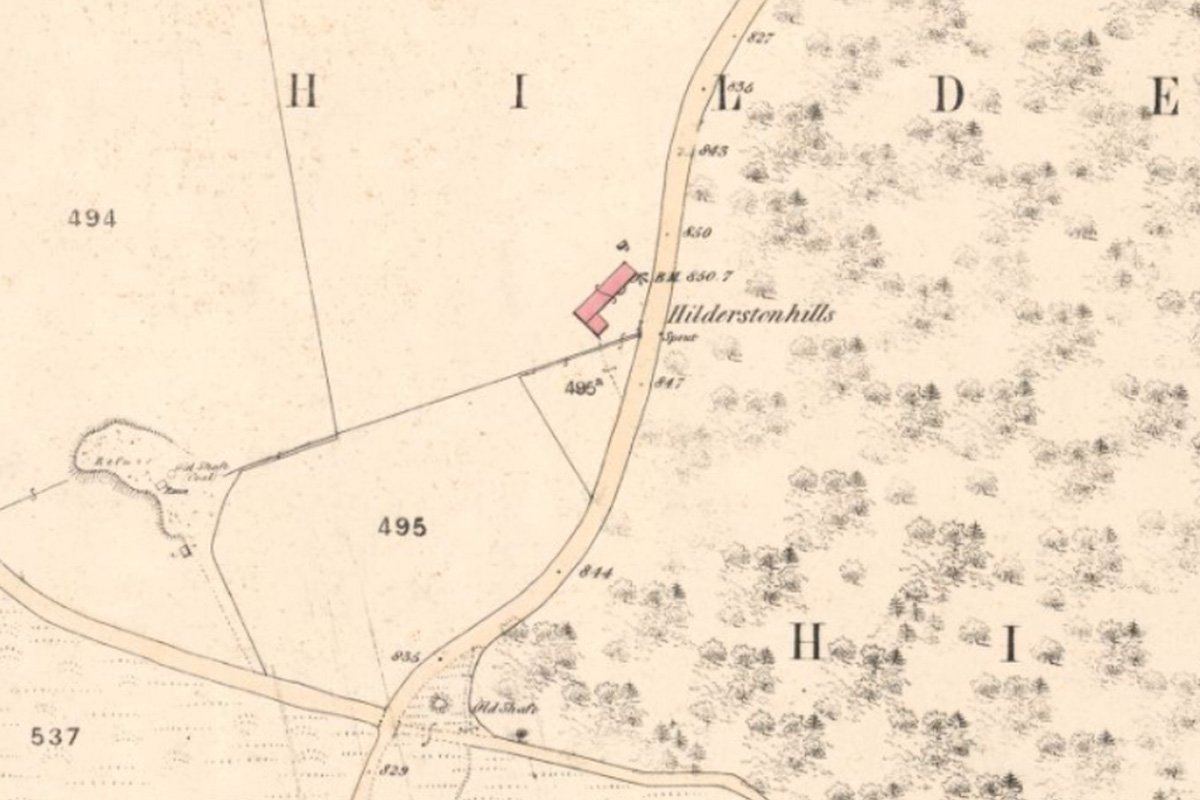

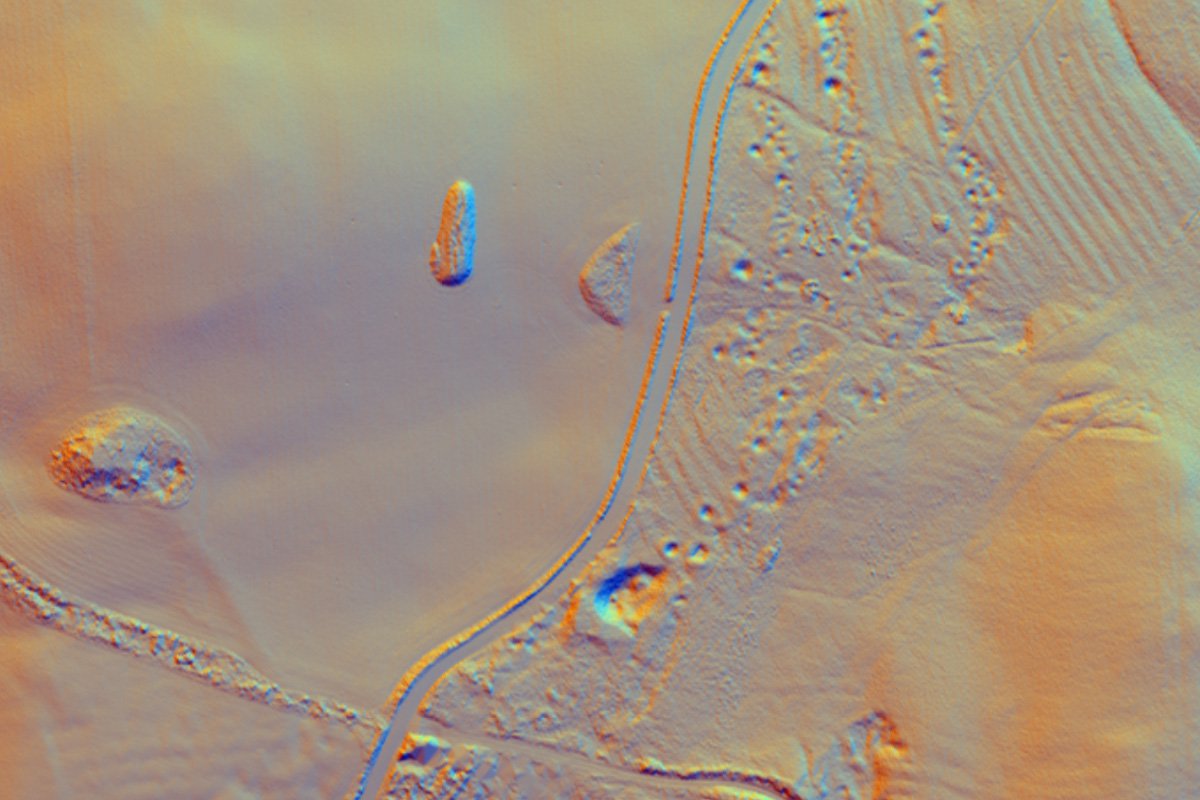

There seems little remarkable about this area of rushes and gorse bushes when viewed from the high road that runs from Ballencrieff Toll towards Linlithgow. However it is worthy of closer inspection. You might pull into the Gordon's View car park, pausing to wonder at the county laid out beneath you, before rambling up the winding track that leads towards the Silvermines quarry. Climbing over the first convenient gate you enter an open expanse of rough pasture that extends from the public road up to the summit of the hill. Walking to the rougher patches of ground that lie close to the road, you find yourself amongst a moonscape of small pits and banks. Each little pit is two metres or so deep, often with a soft rim of moss and bilberry, and a clump of rushes at their centre. There is also one greater crater, six or so metres deep. When viewed from ground level, this landscape appears a random jumble of humps and hollows. However when viewed from above, using the wonders of lidar technology, the pits are seen to line up into three long fingers, marking out where each seam of coal outcropped at the surface.

Coal was probably being worked in the Hilderston Hills by early in the 17th century, when tradition says that a collier named Sandy Maud discovered silver ore beside the little burn south of Cairnpapple. The famous silver mines that developed there had a fairly short working life, but some time later the nearby seams of limestone began to be worked. These quarries at Silvermine became part of a string of limestone workings stretching across the Bathgate hills, which during the 18th and early 19th century produced the huge quantity of lime needed to fertilize and improve newly enclosed lands. The kilns in which the lime was burned consumed great amounts of fuel, and it was fortunate that a good supply of coal lay close at hand in the lands of Hilderston. The narrow track that skirted the hill will once have been a busy highway, with carts and pack horses carrying coal to the kilns and perhaps returning with the finished lime.

Coal will have first been worked where it outcropped at the surface, and from a series of shallow bell pits that extended out a small distance from each shaft. Once the most accessible reserves were exhausted, deeper pits would have been sunk from where in a network of underground workings extended. In an age before practical steam engines, coal was brought to the surface by windlass, or carried on the back of men and women as they climbed to the surface. One of the Hilderston pits is recorded to have been fitted with a spiral wooden staircase. A row of single-room dwellings were built in the shadow of the hill at Hilderston that will have been home to generations of men, women, and children who spend much of their hard lives labouring underground.

The only brief descriptions of Hilderston come from the 1840's and 50's by which time most workings lay derelict and the Hilderston row was largely unoccupied

The surveyors who compiled the first Ordnance Survey maps in about 1855 noted that: “there are a number of old shallow coal pits or diggings scattered about, from 15 to 20 feet deep when coal was obtained in former times, but only superficially, they are all of funnel shape, wide at the top and narrow at the bottom. This description sounds very much like the lines of little pits that survive in the field beside the road, It seems odd however that these were not marked on the very detailed maps that were produced, or have appeared on any subsequent editions of OS map. This raises the thought that the pits might be relatively recent features created by the collapse of workings that lie beneath. However, with perhaps the exception of the big crater, every indication suggested that humps, hollows and the traces of almost a hundred small pits, are the remains of the surface working of coal almost three hundred years ago, at the very dawn of the industrial revolution.