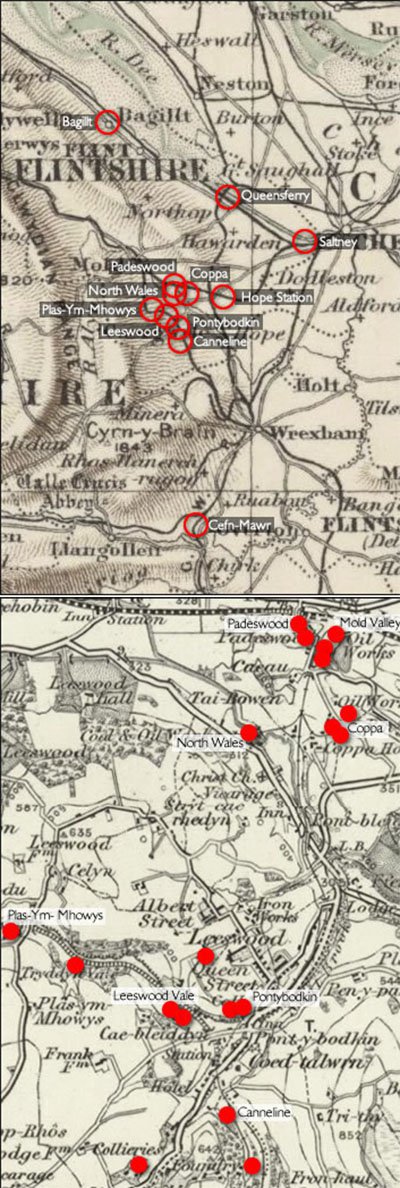

- Bagillt Oil Works

- British Oil Works, Saltney

- Cambrian Oil Works

- Canneline Oil Works

- Coed Talon Oil Works

- Coppa Colliery Oil Works

- Coppa Oil Works

- Coppa Park (Greens) Oil Works

- Dee Oil Works

- Hope Oil Works

- Leeswood Main Oil Works

- Leeswood Vale Oil Works

- Meadow Vale Oil Works

- Mold Valley Oil Works

- North Wales Coal Oil Works

- Oak Pits Oil Works

- Padeswood - Minor Oil Works

- Padeswood Oil Works

- Patent Oil Works

- Plaskynaston Oil Works

- Plas-Ym-Mhowys Oil Works

- Pont-Y-Bodkin Oil Works

- Queensferry Oil Works

- St. David's Oil Works

- Tryddyn Oil Works

- Tryddyn Vale? Oil Works

North Wales

The Coal Oil Industry in Flint and Denbighshire

Overview

During the mid 1860's, the Flintshire area of North Wales was scene of the one of the most extreme speculative bubbles in the history of the British oil industry. Shareholders invested close to a million pounds in a variety of Welsh coal-oil businesses that, within little more than a year, were to have almost no value.

While Scotland, experienced a similar "oil mania", the scale of investment in Welsh oil enterprises was far greater. Much of this capital was raised by joint stock companies that drew on investors from throughout England. There were also many smaller ventures combining the energies of tradesmen, businessmen, professionals and landowners, all following a common ambition to make their fortune as an oil tycoon. An account of 1865 describes the frenetic activity and unreserved optimism evident at the height of the boom, and draws comparisons with the Californian gold rush.

An account of 1868, seemingly by the same author, describes the green valleys of Flintshire after the oil bubble had burst. He paints a picture of an industrial landscape in "suspended animation" with silent oil works and others already falling into dereliction; of hurriedly-constructed structures now subsiding, and others left unfinished following the collapse of trade.

The reasons for the sudden collapse of the industry lie in the international oil trade. In 1851 James Paraffin Young patented his process for producing oil from coal, and established works at Bathgate to exploit the local Boghead cannel coal. Young vigorously defended his patent in a series of high profile court cases and in doing so drew public attention to the merits of his new product. During the late 1850's a substantial coal-oil industry developed in the USA, using processes that infringed Young's patent. The fact that this went forward unchallenged encouraged entrepreneurs, notably Ebeneezer Waugh Fernie, to further test Young's patent in Britain.

A seam of cannel coal, similar in nature the Boghead coal, was first worked in the Leeswood area of Flintshire during the late 1850's. Fernie and a number of other entrepreneurs established oil works in the area from about 1860, initially hoping to escape Young's attention, but ultimately combining under the leadership of Fernie to defend the "Great Paraffin Case" of 1864 . While the court found in Young's favour, this ruling came only months before expiry of Young's patent. The huge publicity given to the court case alerted all to the new opportunities of an unrestricted coal-oil industry. Fernie quickly promoted the Flintshire Oil & Cannel Co. Ltd., the largest of the Welsh coal-oil companies, which in turn inspired formation of over twenty other welsh coal-oil firms during the course of 1864 and 1865.

In 1859, the first oil wells were drilled in Pennsylvania and soon afterwards the first barrels of American crude oil began to be imported into Britain. The outbreak of the American civil war severely disrupted north Atlantic trade and it was not until the end of hostilities in 1865 that unimpeded oil imports began to flood the British market. By 1866, oil prices had fallen to a quarter of their former value. This collapse in market prices led to a chain of debt and the bankruptcy of most coal-oil businesses.

A handful of businesses emerged from the ruins of the industry and continued to produce lubricants and grease for the local market into the 1880's. A number of coal-oil refineries sited close to the River Dee switched to the processing of imported oils and other products, some remaining in production into the 20th century.

- List of Limited Companies associated with the Welsh coal oil industry, from the index of Board of Trade records held in the National Archives

- 1865 Coal Commision report - listing coal and shale oil works known to have been in operation in 1865

- 1868 Trade Directory entries - oil manufacturers in North Wales listed in Slater's Directory 1868

- The Leeswood Accident - a memorial (listing many of the companies and individuals involved in the industry at that time). From The Chester Observer, 11th February 1865.

- Formation of a Welsh Oil Master's Association (listing the major figures in the business at that time). From The Wrexham Advertiser, 14th April 1866

- A History of Petroleum - a short account of the emergence of the Flintshire oil industry, quoting from pamphets on the history of petroleum production. From The Cheshire Observer, 28th January 1865

- Flintshire has Struck Oil, - an account from the early days of the oil boom, drawing parallels between Flintshire and the oil rush towns of the USA and Canada. from Rylands Iron Trades Journal, 11th November 1865

- Petroleum in Flintshire - a brilliant account of the Padeswood area during the height of the oil mania. From The Wrexham Advertiser, 6th January 1866

- On the Manufacture of Coal Oil as conducted in North Wales - a newpaper account of a lecture to the Chemist's Association providing some historical details of the industry. From The Liverpool Daily Post, 9th November 1866

- Ure's Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures and Mines. The entry for "paraffine" describing the technology of oil production at that time, with particular reference to the Flintshire industry. Sixth Edition, Vol. III, 1867

- The Flintshire "Oil-Dorado" - a superb first hand account of the Flintshire oil industry once the oil mania bubble had burst, and an account of the reasons for this collapse. From Oil Trades Review, reprinted inThe North Wales Chronicle, 16th January 1869

- Oil Works and River Poisoning - a letter to the editor responding to accusations of water pollution and highlighting the human cost of collapse of the oil industry. From The Wrexham Advertiser, 30th January 1869

- Travels in Search of New Trade Products, - extract from a book by Arthur Robottom, published in 1893, providing a detailed account of his business dealings in the North Wales oil industry

- The Former Cannel Oil Industry in North Wales and Staffordshire (PDF file) by H.P.W. Giffard. From Oil Shale & Cannel Coal, Proceedings of a Conference held in Scotland, June 1938, Institute of Petroleum.

- The Distillation of Oil from Cannel Coal and Shales, by Harold G. Gregory (web link to the National Library of Wales), Flintshire Historical Society publications, Vol 25, 1971-72

- Young v. Fernie (1) - Opening statement for the plaintiff, (from 29th February 1864). Reprinted in The Journal of Gas Lighting, 22nd March 1864

- Young v. Fernie (2) - Testimonies describing the operation of Leeswood and Saltney oil works. Reprinted in The Journal of Gas Lighting, 22nd March 1864

- Young v. Fernie (3) - Testimonies describing the manufacture of tram oil in South Wales. Reprinted in The Journal of Gas Lighting, 22nd March 1864

- Young v. Fernie (4) - Statement for the defence, (from 22nd March 1864). Reprinted in The Journal of Gas Lighting, 22nd March 1864

- Appeal to the House of Lords - by the Flintshire Cannel Oil & Cannel Co. Ltd. providing detailed descriptions of the company's operations. From The Journal of Gas Lighting, Water Supply and Sanitary Improvement, 3rd April 1866

- Damages by Fire - Davis v. Bagillt Oil Co. Were the stills allowed to overflow?, or where they struck by lightning? From The Wrexham Advertiser, 8th December 1866

- Leeswood - a Treat for Workmen, account of a dinner at Pont-y-Bodkin, featuring a song and speech from the proprietor on the rights of the working man, From The Wrexham Advertiser, 5th January 1867

- The Padeswood Retort Case; a dispute over the cost of constructing retorts at the Mold Valley works; From The Wrexham Advertiser, 23rd December 1871

- Affairs of the Dee Oil Company, account for court proceedings from The Cheshire Observer, 11th March 1893

- Property at Coed Talon - an advertisment for the sale of freehold property in Coed Talon, which provides evidence of the location of some early oil works. From The Wrexham Advertiser 9th June 1866

- P.C. Lawley and the River Alyn Report; accusations of pollution from Pont-y-Bodkin Works and police ineptitude, From The Wrexham Advertiser, 29th December 1866.

- Stealing Pipes. Confusion and dubious deals over the sale of scrap material from Barlow & Jeffs' works. From The Wrexham Advertiser, 16th May 1868

- Leeswood; Telegraphic Communication; a campaign for the introduction of electric telegraph, listing some of the most important firms in the area. Fron The Wrexham Advertiser, 6th October 1866

- Poisoning of the River Alyn; - allegations of pollution against W.B. Marston's Oil Work , From The Wrexham Advertiser, 23rd July 1870

- Pontblyddyn - A Farewell Supper; an account of a dinner in the honour of John Kenny held by fellow employees of Coppa and Plasymhowys oil works. From The Wrexham Advertiser, 5th November 1870

- Alleged pollution of the River Alyn, Bush v. Plas y Mhowys Oil Co. ; a case brought against the PlasyMhowys company which was dismissed as the company had taken measures to avoid reoccurance, From The Cheshire Observer, 27th January 1871

Directories and Lists

General Descriptions

Court Cases

Newspaper Articles

Detailed History

1.) Cannel Coal

The rocks of the coal measures extend in an arc along the eastern edges of Denbighshire and Flintshire; from Llangollen in the south to Point of Air in the north. By the mid 18th century there was already substantial mining activity in areas where coal, ironstone, clay and other minerals lay close to the surface.

At a few locations, seams of cannel coal - a dense, smooth, shale-like variety of coal - were encountered during mining operations. Initially considered worthless, the mineral became highly prized for gas production during the 1840's and subsequently became essential for the production of mineral oil using Young's patent process.

Small reserves of cannel were worked briefly to supply local oil works at Bagillt in Flintshire and Cefn Mawr in Denbighshire, however the bulk of the North Wales oil industry was fuelled by an exceptionally rich form of cannel coal that occurred in the Leeswood district. This was perhaps the mineral described in an account from 1769. (1)

"In sinking some new coal-pits at Leeswood, in the parish of Mold, near the river Alen, was discovered a flat sort of slate, upon which are frequently delineated fossils with as great exactness as an impression of them in plaster of Paris or clay".

A publication of 1840 (2) also makes reference to

"fossils in the collieries of Leeswood in the parish of Mold, and in the black shale incumbent on the coal in other works of the same kind."

William Charles Hussey Jones, proprietor of Leeswood Green Colliery, is credited with the discovery of Leeswood cannel coal in 1858. A paper published in 1866 (3) describes how;

"...all the main coal being exhausted in the take of Mr Henry Jones, a trial was made to prove the lower coal measures, and at a depth of 95 yards below the main coal the famous oil producing cannel was found, much to the astonishment of all people in the neighbourhood."

The paper goes on to describe how the cannel seam was composed of three different type of strata:

- Shale, 1 ft. thick, yielding about 35 gallons of oil per ton and sold at a price of 8s. 6d. per ton

- Smooth cannel, 2 ft. 3in. thick, yielding between 30 and 35 gallons of oil per ton and sold at 9s. per ton

- Curly cannel, 1 ft. 6 in. thick, yielding 90 gallons per ton and sold at a price of 28s. per ton

- Shale, - a further seam 1 ft thick.

Other collieries in the area, including Coppa, Coed Talon, Leeswood Green and Nerquis (4) were soon mining cannel coal to supply the gas trade. A number of limited companies were established, including the Leeswood Cannel & Gas Coal Co. Ltd whose prospectus (5), launched in 1862 stated;

"The Main or Cannel Coal, a peculiar and rare formation, of which, before the discovery at Leeswood, only one known field existed in England at Wigan, and two (the Lesmahagow and Torbane) in Scotland, is now being worked at a depth of only 50 yards from surface, and is above 4ft. thick. The quality of gas produced therefrom is equal to that obtained from the well-known Torbane-mineral, or Boghead, which realises so high as 40s. per ton in Scotland."

Collieries in the Wigan area had, until then, been the principal suppliers of cannel coal in England. A Wigan-based mining engineer was first to publish a cross section of the North Wales coal and cannel field showing "two seams of cannel, one 5ft in thickness" (6) Some proprietors recruited Lancashire colliers as they found "their present workmen inclined to deal too roughly with a substance so much more brittle and valuable than the common coal of the country" (7). The proprietor of the Coed Talon colliery went as far as to state in court "the Welsh people are incompetent to work cannel" (8). This led to a furious exchanges in the local press and instances of mob violence.

With the emergence of the coal oil industry, many oil companies entered into agreements with the established colliery proprietors for the supply of cannel. Such commitments often led to the early bankrupty of these companies when the price of oil collapsed. A few of the larger oil concerns developed or acquired their own cannel mines, and the facility to generate income by selling cannel for gas production enabled some to cling to existence for a period after the oil bubble had burst.

Cannel continued to be mined in Flintshire into the 1880's although dwindling supplies proved ever more expensive to work.

References

- A Description of England and Wales, containing a particular account of each county, by Newbery and Carnan, London, 1769.

- A Topographical Dictionary of Wales 1840, Vol. 1, published by S. Lewis & Co., London 1840.

- The Coalfields of Denbighshire and Flintshire, by Edward Nixon, presented on 13th March 1866, included in the Proceedings of the Liverpool Geological Society, Vol. 1.

- These collieries are listed as producing cannel in Mineral Statistics for 1865, published by HMSO.

- Printed in The Morning Post, 23rd May 1862.

- J. MacKenzie, mining engineer, land and mineral surveyor of Wigan advertised his map and cross sections for sale at 25s. in various newspapers including the Cheshire Chronicle, 28th July 1860.

- Report in the Liverpool Mercury, 7th April 1863.

- Report in the Wrexham Advertiser, 11th April 1863.

2.) Setting the Scene

An account of the Wrexham district (1), published in early 1859, stated:

"Attempts have been made to render available the bituminous shales of this field, which afford paraffine mineral oils & c. of considerable value, although these attempts have not yet been remunerative, having only been carried out very roughly and incompletely, it is far from improbable that a few years hence these shales will become a valuable raw material."

These prophetic words were written immediately prior to the dawning of a new "oil age". At that time, the writer, and most other practical men of science, would have been familiar with petroleum, a natural rock oil gathered from hand-dug wells and natural seepages in many parts of the world. Rangoon petroleum, from Burma, was at that time being imported in limited quantities, mainly for production of paraffin candles. Natural seepages of petroleum also occurred in Flintshire;

"Petroleum or mineral oil is often found in the limestone strata (...in the neighbourhood of Flint...) and is used for medicinal purposes; by the Welsh it is called men ny tylwyth tég or "fairies butter"." (2)

By 1859, coal gas was used to light most major towns, and the manufacturing process, in which coal was heated within a retort, was widely understood. To produce gas sufficiently rich to burn with a strong light in the primitive fish-tail burners then available, cannel coal had to be added to the common coal used in the process. Such cannel was a scarce resource produced at only a few sites in Britain. At that time Chester gas works (3) (and probably most other gas works in the region) used cannel mined in the Wigan area to enrich their gas, however the richest British cannel was widely recognised as the "Torbane mineral" or "Boghead Coal" from Bathgate in Scotland, which achieved an almost mystical reputation and was exported as far as the USA. The production of coal gas yielded a range of by-products, such as tars, bitumen, and naphtha which were refined and processed to produce a range of chemicals.

In 1859, most would have been familiar with "paraffine"; a term loosely applied to describe lamp oils and waxes produced from petroleum or mineral oil. James Young had patented a process to manufacture oils from coal in 1851, and developed techniques at his Bathgate works to produce a range of products including a "paraffine" fuel for oil lamps. By 1859 Young's business was expanding rapidly, sales offices were opening in many British cities, and there was growing public recognition of the man and his patent process. At the same time, a substantial coal-oil industry was operating in the eastern states of the USA, producing oil by processes covered by Young's patent, with some operators paying royalties to Young.

In autumn 1859, the first oil wells where drilled at Titusville, Pennsylvania. Oil fever soon saw a rapid proliferation of wells in Pennsylvania and elsewhere in the USA, and increased production from Canadian oil wells at Enniskillen. This crude oil was soon being shipped in quantity to Britain, 37,082 barrels being imported in 1861, and 362,593 barrels in 1862, (4) much through the port of Liverpool. Disruption of Atlantic trade as a consequence of the American civil war restricted further growth for period. By 1862 American and Canadian crude oil was being refined at Saltney, on the banks of the River Dee.(5)

Imported oils were much cheaper than coal-oil produced under Young's patent, but supplies were erratic, quality was variable, and American crude sometimes proved dangerously explosive. Public attention remained on Young and his paraffine oil, the fame of which spread following further high profile court cases in which the patent was successfully defended. Whereas imported oils attracted little public attention, many entrepreneurs were encouraged by Young's well-publicised success and planned to take full advantage of an unrestricted market following the expiry of Young's patent in 1864.

References

- Wrexham and its neighbourhood by John Jones, reprinted in the Wrexham Advertiser, 19th February 1859

- A Topographical Dictionary of Wales, Vol. 1, published by S. Lewis & Co., London 1840.

- General meeting of the Chester Gas Company, reported in The Chester Chronicle, 5th February 1859

- Petroleum and its products, by A, Norman Tate, published by John W. Davies, London & Liverpool, 1863.

- 400 to 500 casks of American Oil were present when fire broke out at Mr. Charles' grease work at Saltney. Chester Chronicle 26th July 1862

3.) Challenging the Patent

The North Wales oil industry was sparked off by the discovery of a seam of rich cannel coal at Leeswood Green Colliery in 1858. The curly shale part of the seam proved far richer in gas or oil that any other cannel then known in Wales, and shared many characteristics of the famous Scottish Boghead cannel used by James Young. Later tests (1) showed that Leeswood curly cannel yielded 61 gallons of crude oil per ton, approaching the yield of Boghead cannel which under similar conditions produced 72 gallons.

Evidence given at the Young v. Fernie trial (2) tell how Ebeneezer Waugh Fernie first became acquainted with William Charles Hussey Jones,co- proprietor of the Leeswood Green Colliery, in November 1860. Both were in Scotland during the court case in which James Young successfully prosecuted the Clydesdale Chemical Company for breach of patent. Jones seems to have been in Scotland attempting to sell supplies of Leeswood cannel to Scottish oil and gas manufacturers, and was to successfully contract to supply Leeswood cannel to Clydesdale's successors at Cambuslang once production of oil resumed under licence.

Fernie was an accomplished entrepreneur. In court he described himself modestly as "connected with the business of the manganese mines in this country and abroad. I am not a chemist or a scientific man." In fact he had diverse business interests and investments, including directorship of the Ebbw Vale Iron Company and associations with the Coalbrookdale company. He explained that he was "winding up two railways in America immediately before entering upon this oil-making business". It seems highly likely that while in America during 1859 and 1860, Fernie would have become familiar the prosperous coal-oil industry then active in many eastern states, and probably established contacts that would subsequently prove of benefit.

Fernie's first experiments with Leeswood cannel were carried out in 1860 "at the request of the Ebbw Vale company"; other practical tests were carried out at Coalbrookdale, and experimental retorts were set up on Fernie's estate at Berkhamstead in Hertfordshire. In January 1861 Fernie contacted Young intimating that he was preparing to start manufacture of oils, that he considered Young's patent to be unsound, but would be prepared to "receive a licence from Mr. Young under his patent at nominal royalties". Young and his partners offered no variations from their normal terms of licence.

In February 1861, Hussey Jones, of Leeswood Green Colliery, obtained a licence from James Young to produce paraffin oils. No royalty payments were ever made, and while Fernie assured the court that he knew nothing of this licence at the time, circumstances suggest that this provided the means to obtain technical details of Young's patent process. A few days later Fernie and his partners signed an agreement with Hussey Jones, governing the supply of Leeswood cannel to an oil works to be established by Fernie and his partners. Hussey Jones was subsequently to struggle to maintain the level of cannel supplies specified by the contract, and became increasingly indebted to Fernie, eventually losing control of the colliery.

As Fernie began construction of an oil works equipped with 75 retorts, a George Vary (described as "an engineer resident in Bayswater") was sent to Scotland in March 1861 to view Bain's works in Cambuslang, and attempt to gain access to Young's Bathgate works. Although presenting himself as an agent of patent licencee Hussey Jones, Vary was in fact employed by Fernie to gather technical information. Vary also visited the Inverkeithing works of John Scott & Co. , the engineers responsible for construction of much of Young's Bathgate works. Subsequently many of John Scott's workmen were employed to construct retorts and other equipment at Fernie's Saltney works.

Young and his partners became increasingly concerned at reports of espionage, so in spring 1862, Young's partner Edward Binney travelled to Flintshire to gain surreptitious access to Fernie's works and gather evidence of patent infringements. Further information, and samples of the oil produced, was gathered by staff sent down from the Bathgate works later in that summer. By September 1862 Young and partners felt they have sufficient evidence to file a bill of complaint, and eventually an injunction was grant to prevent production by Fernie and his partners (referred to as "The Mineral Oil Company"), until the case could be brought to court.

It not until January 1864 that the "great paraffine case" was brought before the Chancery court lasting 33 days and calling on 73 witnesses. Newspaper accounts commented "the interminable case of Young v. Fernie has completely blocked up that branch of the court. It is, indeed, as this writer says. The Great Case, — the heaviest case which has occurred in our time"(3). Ultimately the court found in favour of Young, with The Mineral Oil Company being required to pay royalties for all past production, plus all court costs.

The extended legal proceedings provided time for Fernie's and his partners to plan a huge public company, the Flintshire Oil and Cannel Company Limited which was launched in July 1864, three months before Young's patent was set to expire. Fernie himself had recognised that the future of the oil industry might lie in oil shale rather than cannel coal and had moved to Scotland to develop oil works at Broxburn and Tarbrax, both opened in 1866. .

While court proceedings record detailed first-person accounts of the history of the Mineral Oil Company, much less is known about other Flintshire oil companies that operated while Young's patent was still in force. Most appear to have deliberately avoided public attention for fear of litigation..

The origins of the Coppa Oil Company are referred to in the autobiography of Arthur Robottom, (4). In a confusing account, written thirty years or so after the event, Robottom describes how he and three friends had purchased Coppa Colliery in the hope of working cannel coal, and became involved in oil production. These early works presumably led to the creation of the Coppa Oil Co. Ltd in 1864.

Even less is known of Canneline Oil Co. Ltd, a major undertaking established in 1861. Young and his partners filed a case for infringement of patent, but this was held in abeyance until the outcome of the Young v Fernie trial was known. The Canneline Oil Co. Ltd. then agreed a settlement with Young and partners for payment of past royalties (5).

References

- Tested by experimental retort at Ebbw Vale, quoted in Court of Chancery; Young and others v. Fernie and others, evidence of Dr. Thomas Anderson, 12th March 1864, reprinted in the Journal of Gas Lighting Vol XIII, 1864

- Court of Chancery; Young and others v. Fernie 1864, reprinted in the Journal of Gas Lighting Vol XIII, 1864. A more detailed commentary and analysis of the case is found in "James Young, Scottish Industrialist and Philanthropist" John Butt, PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 1963. See excerpts of transcripts relating to opening statement by the plaintiff, details of operation at Leeswood and Saltney works, and to the testimony of Ebeneezer Fernie.

- reprinted in The Huddersfield Chronicle 7th May 1864

- from Travels in Search of New Trade Products, Arthur Robottom, 1893, see transcript

- Vice-Chancellors Court, Young and others v. Canneline Oil Co. Ltd, 1864, reprinted in The Journal of Gas Lighting, Water Supply and Sanitary Improvement, 9th August 1864